Resources

1689 Federalism on Galatians (Review of Gordon’s “Promise, Law, Faith”)

On 05, Aug 2022 | In Resources | By Brandon Adams

Posted with permission.

JIRBS 2020 featured a lengthy (46 page) review of T. David Gordon’s “Promise, Law, Faith: Covenant-Historical Reasoning in Galatians.” Gordon offers an interpretation of Galatians from a subservient covenant perspective. Review author Brandon Adams addresses areas of agreement and disagreement with 1689 Federalism, using the book as a launchpad to offer a 1689 Fed explanation of Galatians 3, an often-discussed passage in disputes over covenant theology. He argues that Paul is not simply contrasting the Abrahamic “promise covenant” with the Mosaic “law covenant,” but is rather making an intra-Abrahamic argument by contrasting the distinct promises within the Abrahamic Covenant. This sheds light on Paul’s confusing argument from the grammar of the covenant in Galatians 3:16.

From the conclusion:

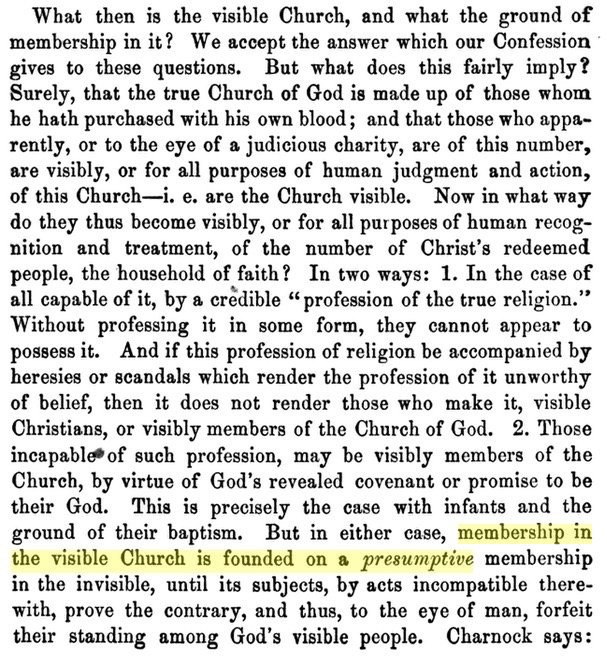

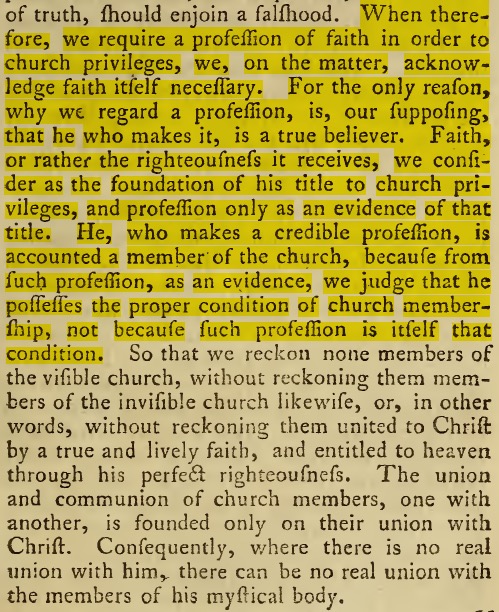

Promise, Law, Faith helpfully challenges the dominant Reformed reading of Galatians by insisting we must understand Paul’s temporal reasoning and his covenant distinctions. The belief that the Abrahamic, Mosaic, and new covenant are all, in substance, the same covenant does not match Paul’s thought in his letter to the Galatians. “[W]e may say with entire confidence that ‘these are two covenants’ (Gal. 4:24) can never be responsibly construed as ‘these are one covenant’” (208).59 Gordon’s recognition that Paul’s citation of Leviticus 18:5 describes the Sinai covenant of works itself, rather than a misunderstanding or abuse of it, is a crucial foundation for the eschatological law and gospel distinction, even though Gordon himself hinders this foundation by too rigidly limiting Paul’s analysis of the Sinai covenant to temporal blessing and curse. Gordon’s division of the Abrahamic covenant into three distinct promises made concerning different seed (carnal, national, corporate seed and singular, Messianic seed) is very helpful in making sense of Paul’s argumentation in Galatians (even if Gordon himself does not draw out all of the necessary implications of this).

Gordon’s denial that justification by faith alone was challenged by the Judaizers, combined with his insistence on the sub-eschatological nature of Paul’s view of the Sinai covenant, however, leads him to misinterpret key passages that are foundational to the doctrine of justification by faith alone as well as penal substitutionary atonement. His doctrine of the moral law is also unnecessarily impaired by defining ὁ νόμος as the Sinai covenant. While I sympathize with Gordon’s goals, I think more care must be taken in balancing biblical and systematic theology.60 In my opinion, the covenant theology of the seventeenth-century particular Baptists61 struck the right balance between biblical theology (including the historia testamentorum—compare WCF 7.5–6 which conflates the biblical covenants as one in substance with 2LBC 7.3) and systematic theology. However, much of that work has been polemical in nature, arguing against paedobaptism. The church would be greatly benefited from more work applying the Particular Baptist understanding of covenant theology to biblical studies. I am thankful for Gordon nudging us in that direction.