Owen

“DOLPHINS IN THE WOODS”: A Critique of Mark Jones and Ted Van Raalte’s Presentation of Particular Baptist Covenant Theology, Samuel Renihan

On 24, Jan 2016 | In Samuel Renihan | By Brandon Adams

In a JIRBS 2015 article, Samuel Renihan critiques a chapter in A Puritan Theology dealing with baptist covenant theology. Renihan demonstrates that Jones and Van Raalte’s failed to adequately understand and present the baptist position.

No one ever loses a debate. Both sides walk away in victory because they stated their cases correctly. The opponent, of course, completely misunderstood and simply didn’t get it. Even the audience agrees. “Our side won.” Sadly, most debates are like this, and debates between paedobaptists and Baptists throughout the years have been no exception to the trend. For many centuries the baptismal debate has divided, disappointingly but necessarily, brothers who otherwise share a great deal in common.

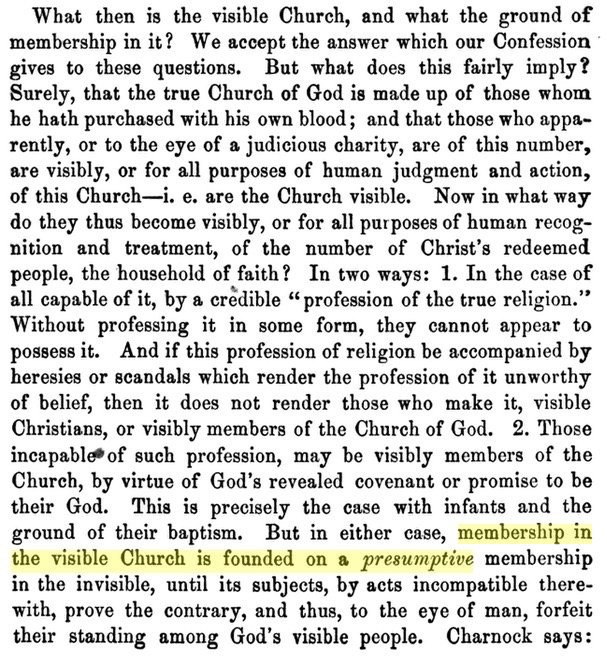

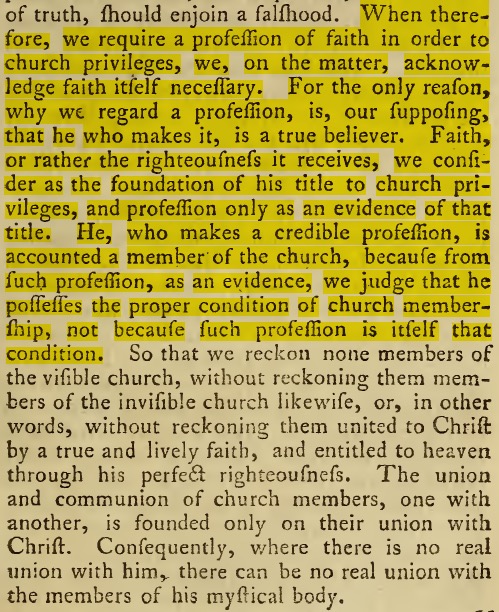

In Joel Beeke and Mark Jones’ massive and delightful A Puritan Theology they have dedicated a chapter to describing this debate as it took place in the late seventeenth century. Their chapter sets out to do two main things: first, to vindicate John Owen’s covenant theology from Baptist appropriation, and second, to demonstrate how John Flavel bested Philip Cary in their printed debate on the subject of covenant theology. This present article will evaluate the portrayal of the Particular Baptists as it is found in that chapter, clarifying how and why the Particular Baptists appropriated John Owen’s covenant theology and demonstrating that while the Cary/Flavel debate is useful for illustration, Cary’s views must be placed within the context of Particular Baptist federalism as a whole—particularly regarding the conditionality of the covenant of grace and the purpose and design of the Mosaic covenant. This evaluation is not intended to revive the debate itself, but rather to present a fairer and more complete portrait of Particular Baptist federalism and their arguments against paedobaptism.

John Owen, Baptism, and the Baptists (Crawford Gribben)

March 20, 2015: Dr. Crawford Gribben, @GribbenC (Professor of Early Modern British History at Queen’s University Belfast and author of the recently published academic biography John Owen and English Puritanism: Experiences of Defeat (Oxford Studies in Historical Theology)) was the guest lecturer at the Strict Baptist Historical Society Annual Lecture which took place in Kensington Place, London. His lecture was titled, “John Owen, baptism & the Baptists.” The lecture was later published in By Common Confession: Essays in Honor of James M. Renihan.

Gribben addresses, amongst other things, the oft-cited tract “Of Infant Baptism.” He notes this was not published until 1721. It was never published in Owen’s lifetime.

(41:00) “Asty does not explain when this tract of infant baptism was written, whether it was intended to be separately published, nor why Owen did not publish it within his own lifetime. The reality is, simply, that Owen may not have been its author. Many of the texts within this edition were taken from manuscripts in Owen’s own hand. But many other items in this volume were taken from auditor’s notes. The tract’s abbreviated form and lack of intellectual development suggests that it may have its provenance in notes of a sermon or presentation Owen made upon this theme. But despite the lack of information about the provenance of the tract, some recent defenders of Owen’s infant baptismal theories have argued that he wrote it very precisely in 1657 or 1658 simply on the basis that Asty’s edition juxtaposes this brief, abbreviated, untraceable tract with a response to John Tombes book “Antipaedobaptism” which was published in 1657. The argument of significance of Owen’s only title focusing on infant baptism is based on some very uncertain presuppositions. The only thing we can be sure of about “Of Infant Baptism” is that Owen did not publish this tract within his own lifetime, that it did not circulate as representing his thinking on this issue for almost 40 years after his death when it appeared in a volume alongside many other texts reconstructed from sermon notes taken by an auditor.”

JOHN OWEN AND NEW COVENANT THEOLOGY

On 17, Feb 2015 | In Richard Barcellos | By Brandon Adams

JOHN OWEN AND NEW COVENANT THEOLOGY:

Owen on the Old and New Covenants and the Functions of the Decalogue in Redemptive History in Historical and Contemporary Perspective

Richard C. Barcellos

John Owen was a giant in the theological world of seventeenth century England. He is known today as quite possibly the greatest English theologian ever. His learning was deep and his writings thorough and profound. He has left the Christian Church with a legacy few have equaled in volume, fewer yet in content. In saying this of Owen, however, it must also be recognized that some things he said are difficult to understand. Some statements may even appear to contradict other statements if he is not followed carefully and understood in light of his comprehensive thought and the Reformation and Post-Reformation Protestant Scholastic world in which he wrote.

If one reads some of the difficult sections of Owen’s writings, either without understanding his comprehensive thought and in light of the theological world in which he wrote, or in a superficial manner, some statements can easily be taken to mean things they do not. When this is done, the result is that authors are misunderstood and sometimes, subsequent theological movements are aligned with major historical figures without substantial and objective warrant. Two such instances of this involve John Owen and New Covenant Theology (NCT).

John G. Reisinger claims that Owen viewed the Old Covenant1 as “a legal/works covenant.”2 He goes on and says:

This covenant was conditional because it was a legal/works covenant that promised life and threatened death. Israel failed to earn the blessings promised in the covenant. But under the New Covenant, the Church becomes the Israel of God and all her members are kings and priests (a kingdom of priests). Christ, as our Surety (Heb. 7:22), has kept the Old Covenant for us and earned every blessing it promised.3

The reader of Owen’s treatise on the Old and New Covenants in his Hebrews commentary, however, will quickly realize that Reisinger’s comments above do not give the full picture of Owen’s position. For Owen did not view the Old Covenant as a covenant of works in itself. He viewed it as containing a renewal of the original covenant of works imposed upon Adam in the Garden of Eden,4 something emphatically denied by Reisinger.5 Neither did Owen teach that Christ “kept the Old Covenant for us and earned every blessing it promised.”6 On the contrary, Owen taught that obedience or disobedience to the Old Covenant in itself neither eternally saved nor eternally condemned anyone and that its promises were temporal and only for Israel while under it.7 According to Owen, what Christ kept for us was the original Adamic covenant of works, not the Old Covenant as an end in itself. Owen says:

The phrase ‘Old Covenant’ will be used throughout as a synonym for ‘Mosaic or Sinai Covenant.’ ↩

John G. Reisinger, Tablets of Stone (Southbridge, MA: Crown Publications, Inc., 1989), 36. ↩

Reisinger, Tablets of Stone, 37. ↩

John Owen, The Works of John Owen (Edinburgh, Scotland: The Banner of Truth Trust, 1991), XXII:78, 80, 81, 89, 142. Owen viewed the Old Covenant as containing a works-inheritance principle of the broken covenant of works. The reintroduction of this element of the covenant of works, however, functioned on a typological level under the Old Covenant and applied to temporal promises and threats alone. See Mark W. Karlberg, Covenant Theology in Reformed Perspective (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2000), 167, 184, 217, 218, 248, 273, 346, and 366 for a similar understanding of the works principle of the Old Covenant as it relates to the covenant of works on the typological level of kingdom administration. ↩

The following is taken from John G. Reisinger Abraham’s Four Seeds (Frederick, MD: New Covenant Media, 1998), 129. In it he denies both the covenant of works and the covenant of grace as traditionally understood. “Some time ago I discussed the basic theme of this book with a group of Reformed ministers that was about equally divided on the subject of Covenant Theology, Dispensationalism, and the view that I hold. Several of those who held strongly to Covenant Theology insisted on using the term covenant of grace as if it had the authority of a verse of Scripture. They made no attempt to prove their assertions from Scripture texts. They kept speaking in terms of logic and theology. I finally said, ‘We agree that the Bible is structured around two covenants. However, the two covenants that you keep talking about, namely, a covenant of works with Adam in the garden of Eden and a covenant of grace made with Adam immediately after the fall, have no textual basis in the Word of God. They are both theological covenants and not biblical covenants. They are the children of one’s theological system. Their mother is Covenant Theology and their father is logic applied to that system. Neither of these two covenants had their origin in Scripture texts and biblical exegesis. Both of them were invented by theology as the necessary consequences of a theological system.’” Though Reisinger denies the Edenic covenant of works, he does not deny the theology of the covenant of works entirely. He simply does not go back far enough in redemptive history for its basis (cf. Hosea 6:7 and Romans 5:12ff). Because of holding to a modified covenant of works position (i.e., the Mosaic Covenant is the covenant of works), Reisinger’s writings uphold the law/gospel distinction which is crucial in maintaining the gospel of justification by faith alone. For this he is to be commended. ↩

Reisinger, Tablets of Stone, 37. ↩

Owen, Works, XXII:85, 90, 92. ↩

RCH, CHAPTER 10 : The Difference Between the Two Covenants

On 04, Dec 2014 | In Resources | By Brandon Adams

[PDF Available Here]

CHAPTER 10

The Difference Between the Two Covenants

John Owen1

But now he has obtained a more excellent ministry, by how much also he is the mediator of a better covenant, which was established on better promises. (Heb. 8:6)2

There is no material difference in any translators, ancient or modern, in the rendering of these words; their significance in particular will be given in the exposition.

In this verse begins the second part of the chapter, concerning the difference between the two covenants, the old and the new, with the pre-eminence of the latter above the former, and of the ministry of Christ above the high priests on that account. The whole church-state of the Jews, with all the ordinances and worship of it, and the privileges annexed to it, depended wholly on the covenant that God made with them at Sinai. But the introduction of this new priesthood of which the apostle is discoursing, did necessarily abolish that covenant, and put an end to all sacred ministrations that belonged to it. And this could not well be offered to them without the supply of another covenant, which should excel the former in privileges and advantages. For it was granted among them that it was the design of God to carry on the church to a perfect state, as has been declared on chap. 7; to that end he would not lead it backward, nor deprive it of any thing it had enjoyed, without provision of what was better in its room. This, therefore, the apostle here undertakes to declare. And he does it after his usual manner, from such principles and testimonies as were admitted among them. Read more…

This is a slightly revised version of Owen’s exposition taken from Nehemiah Coxe and John Owen, Covenant Theology from Adam to Christ (Palmdale, CA: RBAP, 2005) and is used with permission. The footnotes are the ones in the Coxe/Owen volume. Those bracketed with [ ] were provided by the editors of the Coxe/Owen volume. ↩

Νυνὶ δὲ διαφορωτέρας τέτυχεν λειτουργίας, ὅσῳ καὶ κρείττονός ἐστιν διαθήκης μεσίτης, ἥτις ἐπὶ κρείττοσιν ἐπαγγελίαις νενομοθέτηται. Exposition.- Turner remarks that nuni., now, is not here so much a mark of time, as a formula to introduce with earnestness something which has close, and may have even logical, connection with what precedes. See also for this use of the term, ch. xi.16, 1 Cor. xv.20, xii.18, 20; in which passages it does not refer to time, but implies strong conviction grounded upon preceding arguments.- Ed. [Banner of Truth Edition.] ↩

The Oneness of the Church (Owen)

On 24, Nov 2014 | In Resources | By Brandon Adams

Below is an essay from John Owen found in his introduction to his commentary on the book of Hebrews. I’m posting it here for simple reference as I cannot find it anywhere else online as a single, separate article. The text is copied from http://www.godrules.net/library/owen/131-295owen_q3.htm

This essay has very important implications for how to properly interpret the olive tree of Romans 11.

Note that Owen argues against the idea that the nation of Israel was the church. Instead, he argues that the church in the Old Testament was the elect remnant within the nation of Israel. He says there were two offspring of Abraham: physical and spiritual. And there were two types of promises made to Abraham to correspond to these offspring: physical/temporal and spiritual/eternal. And these two types of promises were both covenantal promises. They were both parts of the Abrahamic Covenant. Thus the Abrahamic Covenant is both carnal and spiritual. It existed in a mixed state until the coming of Christ, but it has now been separated. Owen’s essay on the Oneness of the Church should be read in light of the following comment he makes later in his commentary:

When we speak of the “new covenant,” we do not intend the covenant of grace absolutely, as though it were not before in existence and effect, before the introduction of that which is promised here. For it was always the same, substantially, from the beginning. It passed through the whole dispensation of times before the law, and under the law, of the same nature and effectiveness, unalterable, “everlasting, ordered in all things, and sure.” All who contend about these things, the Socinians only excepted, grant that the covenant of grace, considered absolutely, — that is, the promise of grace in and by Jesus Christ, —was the only way and means of salvation to the church, from the first entrance of sin.

But for two reasons, it is not expressly called a covenant, without respect to any other things, nor was it called a covenant under the old testament. When God renewed the promise of it to Abraham, he is said to make a covenant with him; and he did so, but this covenant with Abraham was with respect to other things, especially the proceeding of the promised Seed from his loins. But absolutely, under the old testament, the covenant of grace consisted only in a promise; and as such only is proposed in the Scripture,

EXERCITATION 6.

ONENESS OF THE CHURCH.

1. Oneness of the church — Mistake of the Jews about the nature of the promises.

2. Promise of the Messiah the foundation of the church; but as including the covenant.

3. The church confined unto the person and posterity of Abraham — His call and separation for a double end.

4. Who properly the seed of Abraham.

5. Mistake of the Jews about the covenant.

6. Abraham the father of the faithful and heir of the world, on what account.

7. The church still the same.

The Decalogue in the Thought of Key Reformed Theologians with Special Reference to John Owen

On 17, Nov 2014 | In Resources, Richard Barcellos | By Brandon Adams

The following is Appendix Two in Richard Barcellos’ The Family Tree of Reformed Biblical Theology. Here is a PDF version.

Introduction

In this Appendix, we will explore the thought of John Owen, as well as several other Reformed theologians from the 16th-18th centuries, on the functions of the Decalogue. We will note the various nuances of terminology and theological formulation among Reformed theologians of the past. But we will also see basic methodological and theological continuity from John Calvin to Thomas Boston. This, once again, displays Owen’s continuity with the Reformed tradition and the continuity among the Reformed orthodox on this subject. As will be seen, the Reformed orthodox approached this subject utilizing a redemptive-historical hermeneutic, something we noted in Chapter Six.

Our focus will be upon John Owen. He is not always easy to understand and has been misused on the issue of the functions of the Decalogue. We will seek to allow him to speak for himself, offer some observations, and compare Owen’s statements with those of others before and after him. This will display, among other things, the fact that Owen fits within the broader theological tradition of Reformed thought on the functions of the Decalogue in redemptive history. Read more…

Interactive Outline of John Owen’s Exposition of Hebrews 8:6-13

On 07, Jun 2013 | In Resources | By Brandon Adams

In talking with a number of well read people, I have been surprised how many of them are completely unaware of John Owen’s contribution to covenant theology. I had one person ridicule baptists for rejecting “Reformed orthodoxy” in the Westminster Standards because of our view of covenant theology. He then informed me he would “stick with Witsius, Owen, Petto, and Colquhoun.” This man was completely unaware that John Owen rejected the “Reformed orthodoxy” of the Westminster Standards.

Owen rejected the formulation of the Westminster Confession (one covenant, two administrations) and held that the new and the old were two distinct covenants with two different mediators and everything else that follows. I believe he provides a valuable contribution to current debate over covenant theology and everyone who is interested should read him. However, I also know not everyone has time to read through his 150 pages on Hebrews 8:6-13, so I have created a summary outline of Owen’s argumentation. I created it in a collapsible format to make it easier to follow the progress of his arguments. Hopefully this will interest people in reading Owen, which will hopefully lead to a better understanding of covenant theology for us all.

Here is the link:

Owen on Hebrews 8:6-13 (Collapsible Outline)

Here are a couple of quotes to give you a taste:

The judgment of most reformed divines is, that the church under the old testament had the same promise of Christ, the same interest in him by faith, remission of sins, reconciliation with God, justification and salvation by the same way and means, that believers have under the new… The Lutherans, on the other side, insist on two arguments to prove that there is not a twofold administration of the same covenant, but that there are substantially distinct covenants and that this is intended in this discourse of the apostle…

…Having noted these things, we may consider that the Scripture does plainly and expressly make mention of two testaments, or covenants, and distinguish between them in such a way as can hardly be accommodated by a twofold administration of the same covenant…Wherefore we must grant two distinct covenants, rather than merely a twofold administration of the same covenant, to be intended. We must do so, provided always that the way of reconciliation and salvation was the same under both. But it will be said, and with great pretence of reason, for it is the sole foundation of all who allow only a twofold administration of the same covenant, ’That this being the principal end of a divine covenant, if the way of reconciliation and salvation is the same under both, then indeed they are the same for the substance of them is but one.’ And I grant that this would inevitably follow, if it were so equally by virtue of them both. If reconciliation and salvation by Christ were to be obtained not only under the old covenant, but by virtue of it, then it must be the same for substance with the new. But this is not so; for no reconciliation with God nor salvation could be obtained by virtue of the old covenant, or the administration of it, as our apostle disputes at large, though all believers were reconciled, justified, and saved, by virtue of the promise, while they were under the old covenant.

Having shown in what sense the covenant of grace is called “the new covenant,” in this distinction and opposition to the old covenant, so I shall propose several things which relate to the nature of the first covenant, which manifest it to have been a distinct covenant, and not a mere administration of the covenant of grace.

–

This covenant [Sinai] thus made, with these ends and promises, did never save nor condemn any man eternally. All that lived under the administration of it did attain eternal life, or perished for ever, but not by virtue of this covenant as formally such. It did, indeed, revive the commanding power and sanction of the first covenant of works; and therein, as the apostle speaks, was “the ministry of condemnation,” 2 Cor. iii. 9; for “by the deeds of the law can no flesh be justified.” And on the other hand, it directed also unto the promise, which was the instrument of life and salvation unto all that did believe. But as unto what it had of its own, it was confined unto things temporal. Believers were saved under it, but not by virtue of it. Sinners perished eternally under it, but by the curse of the original law of works.

–

No man was ever saved but by virtue of the new covenant, and the mediation of Christ in that respect.

The Family Tree of Reformed Biblical Theology

Subtitled Geerhardus Vos and John Owen–Their Methods of and Contributions to the Articulation of Redemptive History, this book is a comparative analysis of Vos and Owen in historical-theological context. The thesis is that Vos’ biblical-theological method should be viewed as a post-Enlightenment continuation of the pre-critical federal (i.e., covenant) theology of seventeenth-century Reformed orthodoxy.

Subtitled Geerhardus Vos and John Owen–Their Methods of and Contributions to the Articulation of Redemptive History, this book is a comparative analysis of Vos and Owen in historical-theological context. The thesis is that Vos’ biblical-theological method should be viewed as a post-Enlightenment continuation of the pre-critical federal (i.e., covenant) theology of seventeenth-century Reformed orthodoxy.

324 pages

Published 2010

If you are interested in Reformed biblical theology and how it relates to the federalism (or covenant theology) of the post-Reformation era, this book is for you. It contains a brief history of biblical theology, Vos and Owen in historical-theological context, a comparison between Vos’ Biblical Theology and Owen’s Biblical Theology, then a closing comparative analysis and conclusion.

Available at RBAP

Endorsements

Here is a book no seminary library should be without and which no department of biblical studies, or historical theology can responsibly ignore….Richard Barcellos’ excellent treatment of the hermeneutics of two of history’s greatest biblical scholars should be on your required reading shelf.

Richard W. Daniels, Ph.D.

Author of The Christology of John Owen

Congratulations and gratitude are due to Dr. Richard Barcellos for giving us this wide-ranging, detailed study of the history of biblical theology. With this substantial contribution Dr. Barcellos has put both the academy and the pulpit deeply in his debt.

Sinclair B. Ferguson, Ph.D.

Author of John Owen on the Christian Life

Those interested in Reformed theology, in particular issues of theological method, are indebted to Barcellos for this most welcome and helpful study.

Richard B. Gaffin, Jr., Ph.D.

Professor of Biblical and Systematic Theology, Emeritus

Westminster Theological Seminary